The Gallows

- nicholasjdenton

- Dec 27, 2024

- 8 min read

Updated: Dec 31, 2024

There was a weasel lived in the sun

With all his family,

Till a keeper shot him with his gun

And hung him up on a tree,

Where he swings in the wind and rain,

In the sun and in the snow,

Without pleasure, without pain,

On the dead oak tree bough.

There was a crow who was no sleeper,

But a thief and a murderer

Till a very late hour; and this keeper

Made him one of the things that were,

To hang and flap in rain and wind,

In the sun and in the snow.

There are no more sins to be sinned

On the dead oak tree bough.

There was a magpie, too,

Had a long tongue and a long tail;

He could talk and do -

But what did that avail?

He, too, flaps in the wind and rain

Alongside weasel and crow,

Without pleasure, without pain,

On the dead oak tree bough.

And many other beasts

And birds, skin, bone, and feather,

Have been taken from their feasts

And hung up there together,

To swing and have endless leisure

In the sun and in the snow,

Without pain, without pleasure,

On the dead oak tree bough.

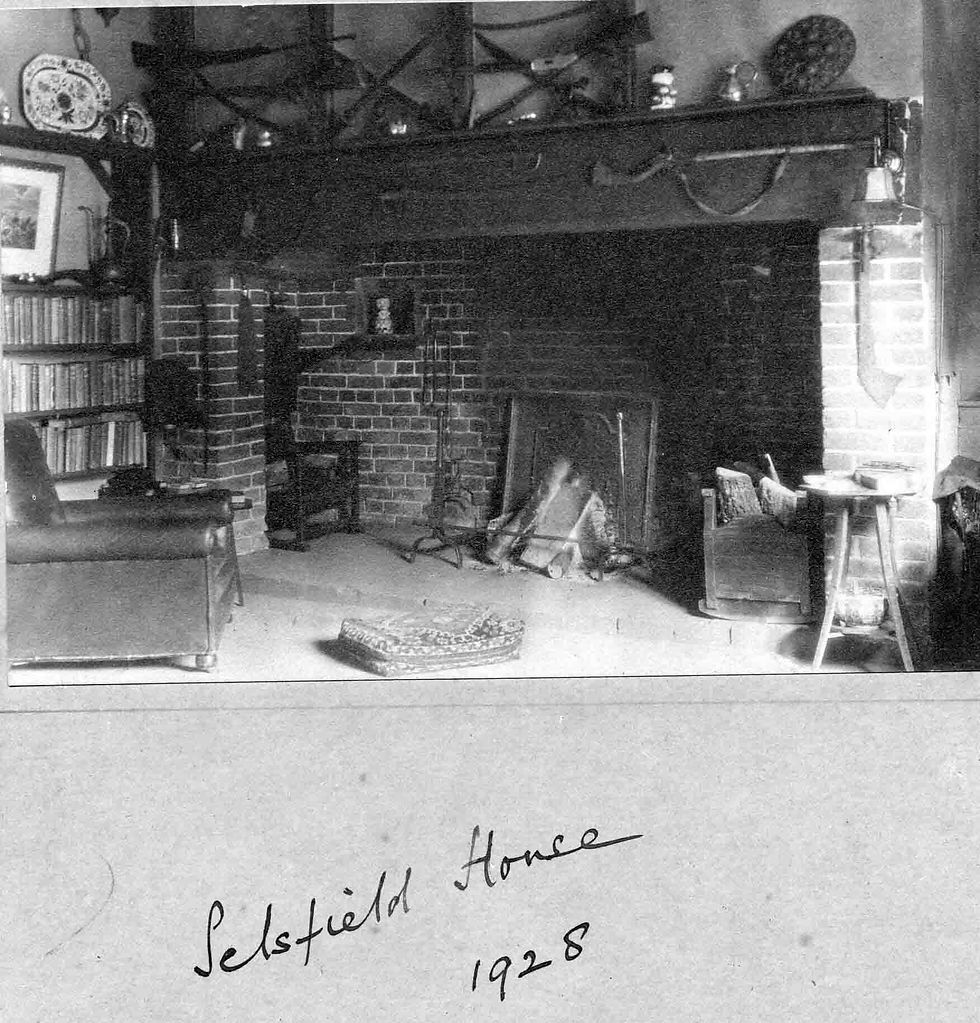

The Gallows was written in July 1916 when Edward Thomas was staying with his friends, the Lock Ellises, at Selsfield House, near Ashdown Forest, after a few days walking in Sussex and Kent with Helen, his wife. As he wrote to his friend, Eleanor Farjeon, he “could not help writing these 4 verses on the theme of some stories I used to tell Baba there”.

He had originally told the stories to his younger daughter, Myfanwy when they had been staying there at Christmas, the year before the war. Towards the end of his notebook of the time, where he normally wrote ideas for future pieces, he had jotted down: “NB tell the 3 ‘horrid stories’ that I told Baby, about the dead crow, weasel & rat”.

Myfanwy remembered the occasion when they had come across a gamekeeper’s vermin pole in her memoir “But this was not a pole but the branch of a tree, hanging low, with his victims strung up to warn off marauding birds and animals from the pheasant chicks he was rearing. The dangling withered carcasses of crows, weasels, jays, and owl and a scarcely recognisable cat, their fur or feathers faded by the rain to earth colour, eyeless and swaying clumsily, filled me with gruesome fascination. ‘Can they feel, do they mind being dead, was that a cat, someone’s own cat, are they cold, why are they there, why are they dead?’

Myfanwy omitted the rat - as did Thomas in his poem where he swapped the rat for the magpie - possibly the rat was too horrid in retrospect!

The family has joined him for Christmas in 1913 after a long absence. He had been staying at Selsfield House, while trying to overcome his depression that had severely affected him at home in the summer and autumn of 1913. His family had arrived on the day before Christmas Eve to stay for a few days and the weather had turned fine. At 8am on Christmas Day 1913, he noted:

“A still white frost, a clear sky w(ith) a crimson sun rising in SE & a few strips of cloud balanced in the South over hills. All clear but not hard.”

The day after Boxing Day was “a warm bright day after slight frost.”

The first verse of the poem about the weasel may therefore reference Thomas with his family in the sun, after a spell of very unsettled weather on his own at Selsfield in the days before Christmas. The other creatures in the poem seem also to have represented a character, probably based on the stories he had told his three year old daughter.

So the second verse, describing the crow as no sleeper, but a thief and murderer, seems to allude to an old story about the house they were staying in. Nearly two centuries before, Selsfield House had seen the denouement of a theft and grisly murder spree in West Sussex.

In May 1735, Jacob Harris, described as either a highwayman or a pedlar, had stolen a coat worth 10 shillings (or possibly some money) from the old Royal Oak Inn in Wivelsfield. Apprehended by Richard Miles, the innkeeper, he had cut his throat and also killed Miles’s wife, Dorothy, and the maid. Miles identified Harris before he died. Harris made his escape to West Hoathly where he holed up in the Cat Inn, a haunt at that time of smugglers. Learning that he was pursued he then fled to nearby Selsfield House where he hid in the wide chimney. The soldiers pursuing him had been drenched in a rain storm that night and, arriving at Selsfield House, lit a fire to dry their clothes. Up the chimney Harris started spluttering with the smoke from below and soon came down into the parlour. After a struggle he was taken to Horsham Jail and following due process was hanged and his body was hung in a gibbet near the scene of his crime. The saga subsequently inspired a ballad “A dreadful murder done at Eventide in Ditchling just by the Common side” and the post, with a red rooster on top, commemorated the site of the gibbet. It became a subject of a local ghost story and myths about its curative powers.

This story would presumably have been well known to the owners of Selsfield House. One can imagine Thomas recounting it to his children round the fire in the parlour that Christmas. And he also seems to have included references to it in his “horrid tale” about the crow for the three year old, Myfanwy. The thief turned murderer and his pursuit, came to the same end as the crow “to hang and flap in rain and wind”. (“Crow” also suggested the red rooster on the post where the gibbet had stood, although there is no indication from his notebooks ET ever visited it.)

In the third verse the magpie’s long tongue may have been another family reference - to Myfanwy who chattered away to herself and others. (She was known as “Polly Parrot” by the friend of the family, Eleanor Farjeon.)

During that Christmas the family would have walked from Selsfield each day. On 27th December they did one of ET’s favourite walks down to the charcoal burners caravan in the Ghyll below Wakefield Place which he wrote about in his poem, The Penny Whistle (see post). There Bronwen, his elder daughter, found the first primroses. Oak trees were and are common on the sides of the Ghyll and it seems likely they saw the vermin on a dead oak at some point during this walk.

The main shooting estate in the vicinity was Paddockhurst, owned by the Cowdray Family since the late Victorian age. They lived in Paddockhurst House, which was later to become Worth Abbey, and much of their estate lay round the adjoining ghylls to the west of The Ghyll, the Ardingky Brook and Balcombe Brook. The “keeper’s larder” may have been on the edge of this estate as they walked down the path on the ridge through Great Strudgate Farm and Newhouse Farm. Or it may have been in the Ghyll itself, which rose at Selsfield House and flowed down to join the Ardingly Brook, a couple of miles south. The estate was otherwise strictly private and would have been difficult to access with no footpaths crossing it.

The vermin pole, also known as the "keeper's museum," or "keeper's larder” was the subject of an article in The Spectator three years before ET stayed at Selsfield. From the piece, which focused mainly on Sussex, it is clear there was a debate about what constituted vermin, what should be protected and whether getting rid of “vermin” in the wholesale fashion of previous generations of gamekeepers was justified.

The author stated that of all the vermin the one that needed most controlling were rats whose ability to breed was “appalling”. Others needed to be prevented from getting into the pheasant run but might do good elsewhere eg weasels controlling rats, birds controlling slugs and snails.

The author was evidently somewhat anthropomorphic in his attitudes, as would befit one of the generation of Kenneth Graham, regarding rats as “one of the bravest, fiercest creatures in the world”, magpies and jays as handsome birds with amusing habits, and weasels as graceful if savage. The article finds that modern gamekeepers “as a rule are better naturalists than they used to be, and less apt to destroy without knowledge and without reason.”

In contrast Thomas had a somewhat negative attitude to gamekeepers. Since the Christmas at Selsfield he had experienced humiliation at the end of the following year in an encounter with a gamekeeper on a walk with Robert Frost at Ryton (from the house that they were staying in with the Abercrombies, called The Gallows). It was a humiliation that some have argued led later to his enlisting in the army. But he had had an ambivalent attitude to gamekeepers since his youth when he had befriended Dad Uzzell, a Wiltshire poacher. He also critiqued his hero, Richard Jefferies’ veneration for keepers in his biography “If it were not for the poacher’s own wit and knowledge that come out in half of the best passages (of Jefferies’ The Gamekeeper at Home), the reader might be excused for disgust with such a policeman god.”

The images in the last verse of the poem go beyond the horrid individual tales towards a more generalised slaughter. This would have been reminscent of the war in France with its trenches and barbed wire with remnants of bodies “hung up there together,/To swing and have endless leisure.” As Edna Longley has pointed out the battle of the Somme had started a few days before he wrote the poem. Although it would have been too early for the mayhem to have been fully realised at home, the artillery barrages laid down in the build up would have been heard from Kent and Sussex. And after nearly two years of war its depredations were already horrifyingly clear.

A walk

The Ghyll which ET enjoyed walking up so much is largely private though there are a couple of paths crossing over it.

You can still walk over the fields from Selsfield Common, down to Great Strudgate Farm and Newhouse farm, following the footpath, a walk which Thomas often did on a late autumnal afternoon after work. There is then a circular walk from Newhouse Farem which takes you across the Ghyll down to Wakehurst Place and then, going though the Place down to the confluence of the Ghyll and the Ardingly Brook. Crossing both you climb up through woods to a field which you follow clockwise round until you reach Paddockhurst Lane. Turn right along the lane until you arrive at a crossroads with Little Strudgate Farm on right. Follow the lane past it down to a small reservoir on left, then carry on up the hill until you arrive at Newhouse Farm again. Then retrace your steps up to Great Strudgate Farm and the paths across the field to Selsfield House.

For more detail on this and other walks round Selsfield House please see posts on The Penny Whistle, The Gypsy, The Source and The Other.

Acknowledgements

Edward Thomas field note books copyright Henry W. and Albert A Berg Collection, New York.

Transcriptions of the Edward Thomas field note books quoted in this blog are available at the Edward Thomas Study Centre.

I have also drawn on Edward Thomas's letters to Eleanor Farjeon in her autobiography The Last Four Years; Edward Thomas's biography of Richard Jefferies; Myfanwy Thomas's Memoirs in As it Was: and The Gamekeeper's black list from The Spectator 19th February 1910.

Thanks to Edna Longley for her insights in her notes about The Gallows from the Annotated Collected poems of Edward Thomas.

Photographs of Selsfield House courtesy of Charles Knowles and Michael Lines.

Also thanks as always to Ben Mackay for editorial support.

Comments